Greece Religion

In scientific studies on Greek religion, which at the beginning of the 19th century. have taken the place of humanistic scholarship, we can summarily distinguish two main strands: on the one hand, the Greek religion falls within the field of antiquities and the work of scholars of classical antiquity by KO Müller, by FG Welcker, L. Preller etc.. up to E. Rohde, U. Wilamowitz and his contemporaries it led to an analytical elaboration of all the material; on the other hand it concerns the comparative history of religions which seeks to frame it in broader perspectives; the school by FM Müller represented a first step with the comparison of the religions of the Indo-European-speaking peoples, while the subsequent ethnological and evolutionary orientation, with W. Manhardt, A. Dieterich, JG Frazer and others, he drew Greek religion into the orbit of universal comparison. If the philological approach threatens to close the religion of ancient Greece into an anti-historical isolation, comparatism, in turn, often tends, in a no less anti-historical way, to reduce it to generic elements common to many other religions, canceling its specific character. Against both dangers, modern studies try to grasp the meaning of Greek religion in its particular historical development using the method of a comparison conducted with historical criteria.

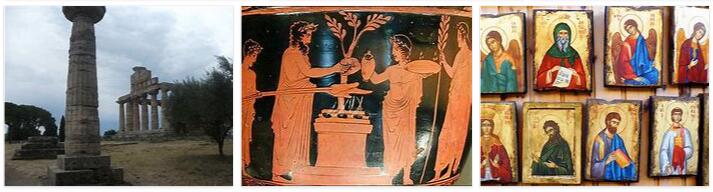

The Greek religion is a polytheism that arose through a long process of formation in which pre-Hellenic elements, of Mediterranean and Eastern origin, merge with elements typical of the Indo-European populations settled in the peninsula, especially the Mycenaean ones. Given the absence of sacred texts, the literary sources on religion are, originally, represented by the poets, by Homer in the first place. However, despite the richness of the mythological and ritual content, Homeric poetry cannot be considered as a faithful mirror of the Greek religion of the time, above all because it makes a conscious selection of religious material, ignoring its popular or too dark aspects. But it is precisely with this tendency to sublimation that the Homeric epic embodies, for the first time, a constant and decisive aspect of Hellenic religious history: in its official and civic form, the religion of the various Greek city-states is always concentrated around the perfectly anthropomorphic and well-defined figures of the Homeric deities. The epic does not yet know of built temples; places of worship are particular places of nature or the homes of kings. But the anthropomorphic divinity requires a dwelling in accordance with its proportions and its character, and is born, profoundly different from the immense sacred oriental constructions, places of worship are particular places of nature or the homes of kings. But the anthropomorphic divinity requires a dwelling in accordance with its proportions and its character, and is born, profoundly different from the immense sacred oriental constructions, places of worship are particular places of nature or the homes of kings. But the anthropomorphic divinity requires a dwelling in accordance with its proportions and its character, and is born, profoundly different from the immense sacred oriental constructions, the Greek temple which almost always houses a single deity. Later it also requires the statuary image, in which human form and divine essence coincide.

In Hesiod the absolute supremacy of Zeus, already repeatedly mentioned in the Homeric poems, becomes, as later in Aeschylus and Pindar, the basis of the whole Olympic system: that this is the result of a historical process, results from the relative scarcity of ancient Zeus feasts and by the originally autonomous sovereignty of other divinities in certain places (Hera in Argos, Athena in Athens, Apollo in Delos and Delphi, etc.). The autonomy of the city-states of the archaic Greece leads to a multiplicity of particular forms of worship, which, however, do not depart from the common spirit of Greek religion in their broad lines.

With the development of industry and commerce and the entry of the popular masses into public life between the 7th and 6th centuries, by means of tyranny, and from the 5th century. in the classic form of democracy, changes also occur in the religious field: ‘new’ types of worship (actually very ancient, but remained outside the state), mysterious and orgiastic, and ‘new’ divinities such as Demeter and Dionysus come to occupy pre-eminent positions in the public religion. Eleusis, where an initiatory cult centered around Demeter and Persephone was probably practiced since the Mycenaean eranow incorporated into the Athenian state, it gradually acquires universal resonance in the Greek world. Although it does not have an immediate influence neither on the public forms of religion nor on the religious practices of the masses, a tendency towards reflexivity and internalization should not be underestimated since the 6th century. BC manifests itself in the Greek consciousness.

Philosophy, placing itself from a rationalistic and moralistic point of view in the face of myth and worship, naturally finds much to criticize in it; on the other hand, the demands of a more individualistic conscience are no longer resigned to the unalterable equilibrium of the divine world. Therefore, the process of corrosion of classical Greek religion begins on two sides, which in Hellenism will manifest itself with the spread of philosophical rationalism on the one hand and of mysticism on the other. Orphism, which takes on historical consistency in the 6th-5th century. BC, it represents an expression of the mystical tendency. During and after the Peloponnesian War the Greek people open their doors, more and more widely, to oriental cults (Phrygians, Egyptians, etc.) which correspond to popular tendencies not sufficiently channeled into civic religion. From the East, even before the rise of Alexander the Great, the need to project onto a living person – the sovereign – the soteriological aspirations by now widespread in the masses, also draws nourishment, adapting the forms of heroic worship to the veneration of exceptional people. The Greek religion, even in these now compromised forms, imposes itself on the Hellenistic ecumene, entering into syncretistic formations with the other religions of the environment. It survives until the advent of Christianity and, subsequently, in disintegrated forms, in folklore. even in these now compromised forms, it imposes itself on the Hellenistic ecumene, entering syncretistic formations with the other religions of the environment. It survives until the advent of Christianity and, subsequently, in disintegrated forms, in folklore. even in these now compromised forms, it imposes itself on the Hellenistic ecumene, entering syncretistic formations with the other religions of the environment. It survives until the advent of Christianity and, subsequently, in disintegrated forms, in folklore.